At the Mennonite Church USA convention in Orlando in July, planners tried something new. Something they called MennoTalks. Not quite TED and not exactly Pecha Kucha, MennoTalks explored a different topic each day, featuring speakers from diverse perspectives. Topics included Celebrating Women (Wednesday); Race, Religion and Justice (Thursday); and Local and Global Peacemaking (Friday). Over the next several weeks, we’ll be featuring a series of posts based on the MennoTalk presentations in Orlando.

At the Mennonite Church USA convention in Orlando in July, planners tried something new. Something they called MennoTalks. Not quite TED and not exactly Pecha Kucha, MennoTalks explored a different topic each day, featuring speakers from diverse perspectives. Topics included Celebrating Women (Wednesday); Race, Religion and Justice (Thursday); and Local and Global Peacemaking (Friday). Over the next several weeks, we’ll be featuring a series of posts based on the MennoTalk presentations in Orlando.

Hannah Heinzkehr is the Executive Director for The Mennonite, Inc. She lives in Goshen, Indiana, with her husband, Justin, and two kids. Hannah’s MennoTalk was categorized under the topic Celebrating Women.

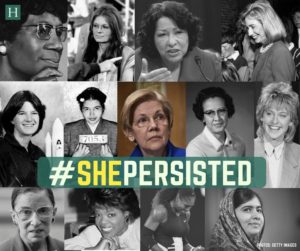

Regardless of your political leaning, it’s likely that you have seen the phrase, “Nevertheless she persisted” floating around. It was first used when the United States Senate took a vote to formally silence Senator Elizabeth Warren as she was protesting an appointment. As Senate Majority leader Mitch McConnell explained the vote, he said that Warren had been warned several times to stop speaking, but “nevertheless, she persisted.”

Regardless of your political leaning, it’s likely that you have seen the phrase, “Nevertheless she persisted” floating around. It was first used when the United States Senate took a vote to formally silence Senator Elizabeth Warren as she was protesting an appointment. As Senate Majority leader Mitch McConnell explained the vote, he said that Warren had been warned several times to stop speaking, but “nevertheless, she persisted.”

As so often happens these days, this phrase quickly took on a life of its own.

The catch phrase — meant to communicate disobedience or a lack of decorum — in fact became a mantra that symbolized and celebrated the ways that women have been persistent in breaking barriers despite attempts to silence them or ignore what they have to say.

Similarly, Womanist theologians, whose work centers the stories and experiences of black women in particular, have sometimes used the phrase “making a way out of no way,” to describe the ways that women of color have persisted despite the multiple layers of oppression that they face — sexism, racism and more. Theologian Monica Coleman describes the act of “making a way out of no way” as the “quest for health and wholeness in the midst of violence, oppression and evil.”

In many contexts, and sometimes against what seems like all reasonable odds, women have illustrated a resilience and a will to persist. This is true in Mennonite Church USA as well. And finding ways to lift up and tell the stories of the women among us who have paved the way for the work of women in leadership in the church today is a critical exercise.

A 2009 audit of women in ministry across Mennonite Church USA revealed that we still had a long way to go. In 2009, 20 percent of Mennonite pastors were women. Today, only three out of 18 area conferences are led by women and none of the six churchwide agencies is headed by a woman (I am the Executive Director of a The Mennonite, Inc., which is an organization of MC USA and I do meet regularly with agency CEO’s). To my knowledge, only one woman of color has ever served as a conference minister and none have headed a churchwide agency.

In 2009, these statistics were striking enough that they led to the formation of the Women in Leadership Project, a group that is still working today to help the church take a closer look at the deep roots of sexism, racism and other forms of oppression and the places where they intersect in our own denomination.

In my own role as a denominational leader, I was lucky to follow another young, female leader, Anna Groff. But prior to Anna stepping into her role, there was only one other woman (and no women of color) who had served as an editor for a Mennonite denominational publication.

Many times over the last few years, I’ve heard people say some version of the following statement: “But we’ve answered the women in leadership question in our denomination. This is no longer a concern.” Often the statement is not that blatant, but the sentiments are there, as if addressing systems of oppression and changing deep-rooted organizational cultures is as simple as changing our denomination-wide statements (although admittedly sometimes that has/might help).

As I’ve talked with, interviewed and read blogs from women across Mennonite Church USA, I am struck by the many stories I hear about what we call microaggressions — subtle and indirect actions or statements that communicate discrimination — that take place on a day-to-day basis.

As a straight, white woman, I know that I have likely been both the recipient and the purveyor of microaggressions.

Here are a few recent real-life examples of microaggressions that have been shared with me and that I have permission to share:

- A reader of a publication sends a letter to the editor, expressing dismay that the quality of the writing in the publication is declining and he’s prepared to drop his subscription. When the editor responds to him, asking for examples, he cites eight articles — all of them written by women and people of color — and states that the writing is “generically clumsy and unpolished.”

- In the middle of a presentation, during time for discussion, an audience member approaches the presenter, a young woman, and remarks that her skirt seems a bit too short and she might want to reconsider the ways that she is dressed when presenting in church settings. The presenter spends the rest of her seminar paranoid about how she is dressed and distracted.

- After an Asian-American leader preaches a sermon to a majority white congregation, several congregation members come up to her and compliment her on her great use of English and her lack of an accent. The presenter is a third generation American citizen.

- During a public meeting, a team leader introduces all of the members of his team by name and job title, except for the youngest, female member of his team who is pregnant. Instead of talking about her work, he mentions the upcoming birth of her baby and thanks her for “continuing to build the Mennonite church.”

This list could go on. My guess is that many of you could share similar stories.

The truth is that systems of oppression aren’t just maintained by blatant hate-filled acts. They are propped up by microaggressions like these, often perpetrated by well-intentioned people and our unwillingness to name microaggressions and see them for what they are.

These are fault lines that split the surface of our organizations and churches.

When he was speaking about the experience of the Israelites under invasion and occupation, the prophet Jeremiah said, “They have treated the wounds of my people carelessly, saying ‘Peace, peace, when there is no peace.’ Thus says the Lord, ‘Stand at the crossroads, and look … and ask for where the good way lies; and walk in it.”

If we truly want to celebrate women and their gifts in our church, it will mean taking an ongoing, introspective look at ourselves — standing at the crossroads — and asking where the good way lies and what systems of oppression are preventing us from walking that road. It will mean not being satisfied with an apparent peace or lack of conflict that masks a churning undercurrent of microagressions.

As I was working on this talk, I tried to think about what a good term for the opposite of a microaggression would be and couldn’t think of anything catchy. But I think it is vitally important that we not only practice naming microaggressions when they occur, but that we start to cultivate and call out behaviors and traditions that do the inverse — behaviors that support and raise people up.

Here are a few recent examples that can provide encouragement in this work:

- A conference minister chooses to step down from a denomination-wide committee in order to make space for more women and people of color from his conference to participate in the conversation.

- An older woman who has served as a pastor and a denominational leader builds time into her schedule at least once a week to intentionally mentor younger women working for the church.

- A congregation takes time after a Sunday worship service to write notes of encouragement and affirmation for denominational staff that celebrate the places where they have noticed the inclusion and contributions of more diverse voices in denomination-wide communications.

- A board chair internationally invites, affirms and makes space during meetings for tears, laughter and anger — not shying away from emotional conversations with people of all genders.

Sharing these examples is both an act of remembering and an act of continuing to carve out possibilities for all of the women who are working to “make a way out of no way” in our church systems today.

Where in your own communities today do you see microaggressions that need to be named? Where do you see behaviors that need to be celebrated?

Too often, oppressive systems end up pitting marginalized people against one another, and this has certainly been true in the ways that women in the church have interacted.

Indigenous Australian activist and artist, Lilla Watson, famously said, “If you have come here to help me, you are wasting your time. But if you have come because your liberation is bound up with mine, then let us work together.”

May our acts of celebrating women be a sign of our continuing, persistent work to move towards liberation together, step by step.