By Janie Beck Kreider

![]() This is part three of four in a series featuring Mennonites working with immigrants. Projects featured in this series received grants from a special offering received at Mennonite Church USA’s 2013 convention in Phoenix toward the DREAMer Fund. These projects were chosen as grant recipients because they have a strong history of working with immigrants in their communities, especially with undocumented individuals and families who suffer from inhumane conditions in detention centers and unjust treatment in working environments.

This is part three of four in a series featuring Mennonites working with immigrants. Projects featured in this series received grants from a special offering received at Mennonite Church USA’s 2013 convention in Phoenix toward the DREAMer Fund. These projects were chosen as grant recipients because they have a strong history of working with immigrants in their communities, especially with undocumented individuals and families who suffer from inhumane conditions in detention centers and unjust treatment in working environments.

“For I was hungry and you gave me something to eat, I was thirsty and you gave me something to drink, I was a stranger and you invited me in, I needed clothes and you clothed me, I was sick and you looked after me, I was in prison and you came to visit me” (Matthew 25:35-36).

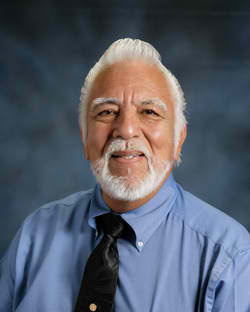

“We’re just a small church doing what we can,” says Lupe Aguilar, pastor of Iglesia Menonita Rey de Gloria (King of Glory), a South Central Mennonite Conference congregation in Brownsville, Texas. This is his refrain when speaking about the work of his community. “We’re not organized or incorporated. We don’t have a creed. We’re a church, and we do what we can.”

The congregation of Rey de Gloria formed in 1999 around a commitment to working with undocumented people and serving those who might otherwise fall through the cracks. They help people find housing, offering places to stay in the church or by hosting people in their homes. With the help of Mennonite Central Committee (MCC), they offer health kits, clothing and food. They give people rides to work, help children get to school, take them to the doctor and connect them with the services they need. “Anything you can imagine,” says Aguilar.

“The majority of my church is undocumented,” says Aguilar. “So we have the undocumented helping themselves.”

Every summer they provide a free daycare service. Many kids who attend are U.S. citizens, but their parents are undocumented. The daycare provides breakfast, lunch and a snack before they go home, “because they probably won’t have a meal when they get home,” explains Aguilar.

Rey de Gloria members also teach carpentry to people who come to the community without a skill. They offer instruction in roofing, dry-walling and painting, among other things. One ‘graduate’ of the program became a contractor and built a large shed behind his house where the church now meets.

Difficult encounters

Word has traveled about Aguilar and his small congregation, which has an attendance of 40 to 60 on any given week. People in the community know that this is a safe place to go for help, and they come asking for “el pastor de Rey de Gloria.” “They call me that,” says Aguilar. “But it is not just me. We’re working together.”

“I’ve got stories galore,” he says, sharing accounts of violence, unjust treatment and heartbreak experienced by people he has accompanied and of the risks they have taken to survive.

I was going down a long street close to my house, and there was a lady waiting for the bus. I stopped and noticed she was crying. I told her the bus wouldn’t come anymore — it was late. She told me she had worked that day from 6 a.m. until 7 p.m., and the lady had given her 10 dollars. After bus fare it would have been a profit of eight dollars. So I took her home and gave her 20 dollars.

Somehow my name got around, and a woman contacted me from Sioux City, Iowa. She was undocumented, and her two kids were being detained near here; she had sent them across the border with a coyote. She wanted to come down to Brownsville to pick them up, so we went to pick up her kids. It was so dangerous to cross the river, and her children had crossed alone.

One woman was raped in front of her husband, and he was beaten to the point of death. They were sure it would happen, so she was taking birth-control pills.

Another woman was raped and became pregnant; she had the baby, but it died. We had to bury the baby, so we found some money to prepare the body for burial. The baby was buried in a pauper’s graveyard, where you have to dig the grave yourself. I distinctly remember how we dug the grave. I was down inside the grave, and I asked her to hand me the little box — a small cardboard box the size of a Bible — and she didn’t want to let it go. It is a sad situation that repeats itself time and time again.

Two girls from El Salvador gathered enough money to pay some men to help them get past the checkpoint 100 miles north of Brownsville. The girls were in a hotel room being abused by these men, and the men wanted more money. The girls called us, and we went in and got the girls and another boy who was there. The guys were drunk and didn’t stop us. We were taken into custody by border patrol because the undocumented girls were with us. We were locked up by the patrol. Of course we were let go; we were not smugglers. The girls were deported, and we are still in contact with them.

A call for compassion in action

Aguilar notes the visible and urgent needs of the undocumented people he encounters. “They have such little access,” he says.

And yet, in Aguilar’s experience, very few Christian congregations have been willing to lend a hand or support Rey de Gloria in their work. “I have experienced a lack of sympathy from many in the church,” he says. “We see each other every day — the documented and the undocumented. And there are so many of us who could help them, but don’t.”

“I came to the Lord at Iglesia Menonita del Cordero,” Aguilar recalls. “I was taught that I was supposed to serve.”

“Every one of us has the right to dignity,” he continues. “More congregations and organizations should be working with the undocumented. Our Lord Jesus was undocumented in Egypt with his family.”

“We are just a church that does what it can,” he repeats. “And there is work to be done.”

###

Image available:

Lupe Aguilar, pastor of Iglesia Menonita Rey de Gloria in Brownsville, Texas.