Jason Kauffman is director of Archives and Records Management for Mennonite Church USA.

“P.S. Change is not always a sign of growth but could also be a sign of shriveling, death, and decay.”

This is how one chorister from Ohio ended his six-page letter to Mary Oyer in 1963. It crossed her desk at Goshen College just before the Church Music Conference convened on campus on April 19-20. The purpose of the conference was to provide a venue for discussion about music in the Mennonite church and the place of instruments — specifically the pipe organ — in worship. It took place during the early stages of planning for a new hymnal, to be published through the collaboration of the (Old) Mennonite Church and the General Conference. As planning continued, the pipe organ emerged as a point of contention about what it meant to be Mennonite in a changing world. The quote above suggests that these debates carried practical and theological implications that extended far beyond the place of instruments in Mennonite worship.

I’m new to the archives, so I’ve been spending a lot of time learning about our collections and thinking about ways to connect them to things happening now in the denomination.

When I heard about the new Mennonite song collection being planned for publication in 2020, I became curious about the work of previous hymnal committees and the issues they faced.

While I grew up singing from the red and blue hymnals, I never stopped to think about the history of their creation or to consider that the process of creating them could be potentially divisive.

But I also know that Mennonites care a lot about music and are proud of this part of their heritage. One indication of this is the volume of documentation that hymnal committees have produced during the 20th century. Not counting the personal papers of several individuals, the Mennonite Church USA Goshen Archives currently houses over 45 boxes of records documenting the activities of hymnal committees from 1902 to 1992. Within this collection, the 1969 hymnal project is the best documented.

As I read through the chorister’s letter to Oyer, I started to think about the role music and singing have played in defining what it means to be Mennonite, both in North America and globally. Letters like these also make me think about how and why these definitions have changed over time as well as the many ways that people have made sense of and responded to these changes.

As the main person responsible for planning the conference, Oyer sent hundreds of invitations to Mennonite ministers and choristers across North America. The man from Ohio wrote to send his regrets, but he also took the opportunity to voice his opinions about the growing popularity of pipe organs in worship. His list of concerns about organs included their high cost, a fear that the organ would draw focus away from worship, and a related fear that organ accompaniment would stunt the ability of Mennonite youth to read and learn music.

On the surface, the letter is about organs in worship, but it’s pretty clear that the author’s objections were also linked to some of his own anxieties about changes that were taking place in the broader Mennonite church.

For example, one of his suggestions for solving the (perceived) problem of declining quality in congregational singing was to reinstate the practice of “separating the sexes on different sides of the church.” In his words, “How can a child learn to sing parts when they hear adults all around them sing four different parts and … the part they want to sing is not too clear…?” Later in the letter, however, he revisited this point, developing a six-part argument for why men and women should sit on opposite sides of the sanctuary. Only one of his arguments directly related to music in worship.

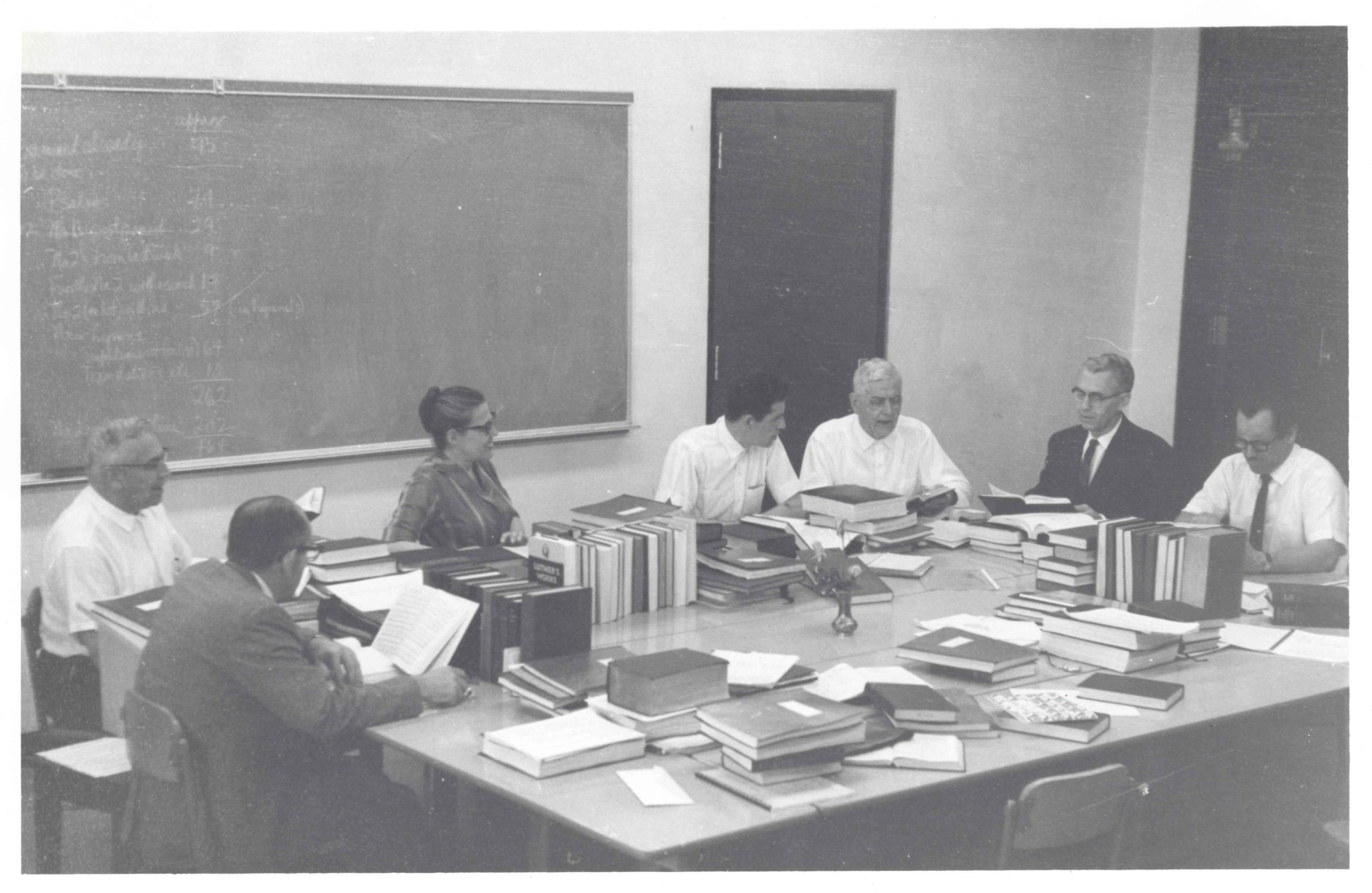

Change and adaptation to change are two familiar refrains for North American Mennonites. In the world of Mennonite music — one traditionally dominated by men, at least at the institutional level — Mary Oyer was a catalyst for change. Out of 10 members of the Joint Hymnal Committee which planned the 1969 hymnal, Oyer was the only woman. After 1970, Oyer also played an instrumental role in expanding the canon of Mennonite music beyond “traditional” hymns to include African American spirituals and the musical traditions of Mennonites and other Christian communities in Asia, Africa and Latin America. Many of these hymns were included in Hymnal: A Worship Book (1992).

People like Oyer have embraced change and, in the process, have done much to expand and enrich our collective definition of what it means to be Mennonite.

A meeting of the Joint Worship and Hymnal Committee. This committee produced the 1969 Mennonite Hymnal, with Mary Oyer acting as Executive Secretary. Starting from bottom left, and moving clockwise around table: Ed Stoltzfus, Paul Erb, Mary Oyer, John Ruth, Chester Lehman, Marvin Dirks, and Walter Klaassen. ~1963-1967

The new songbook committee will build upon this legacy by creating a collection of music that takes “into account the breadth of the Mennonite Church, the diverse ways Mennonites sing and worship, and new digital technologies,” including two separate electronic editions, “one with notated music and one with just the words.”

I suspect that these plans will generate resistance from some in the Mennonite community. Will singing music from a screen (without notes!) dilute the rich Mennonite tradition of four-part, acapella singing? Does this use of technology conform too closely to the patterns of this world? These are legitimate questions and ones that we need to take seriously. But, if history is any indication, I predict that Mennonite musical traditions will continue to grow in strength and diversity, weathering this latest period of change without “shriveling, death, [or] decay.”