At the Mennonite Church USA convention in Orlando in July, planners tried something new. Something they called MennoTalks. Not quite TED and not exactly Pecha Kucha, MennoTalks explored a different topic each day, featuring speakers from diverse perspectives. Topics included Celebrating Women (Wednesday); Race, Religion and Justice (Thursday); and Local and Global Peacemaking (Friday). Over the next several weeks, we’ll be featuring a series of posts based on the MennoTalk presentations in Orlando.

At the Mennonite Church USA convention in Orlando in July, planners tried something new. Something they called MennoTalks. Not quite TED and not exactly Pecha Kucha, MennoTalks explored a different topic each day, featuring speakers from diverse perspectives. Topics included Celebrating Women (Wednesday); Race, Religion and Justice (Thursday); and Local and Global Peacemaking (Friday). Over the next several weeks, we’ll be featuring a series of posts based on the MennoTalk presentations in Orlando.

Chantelle Todman Moore is co-founder of unlock Ngenuity a consulting, coaching and therapy business. Previously, she served as the Philadelphia program coordinator for Mennonite Central Committee and as a program director at both Oxford Circle Christian Community Development Association and Eastern University. Chantelle holds a Bachelor of Arts in International Community Development from Oral Roberts University, a Master of Business Administration in International Economic Development from Eastern University. She is also a qualified administrator for the Intercultural Development Inventory (IDI). She is passionate about embracing diversity and difference as a gift, seeking justice as a mandate and being moved to act by love. She lives in Philadelphia with her spouse, Sam, and their three daughters. Chantelle’s MennoTalk was categorized under the topic Race, Religion and Justice.

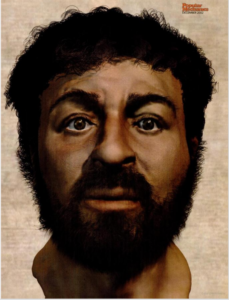

Growing up, if you had asked me to describe the way Jesus looked, I would have listed features such as kind, gentle blue eyes; light brown, flowing hair; and pale, white skin. This is the Jesus I was introduced to through the church. I wonder why it was so important for Jesus to be portrayed like this. Instead of like this.

Medical artist Richard Neave and his team created this drawing of Jesus based on anthropological and archaeological data from Jesus’ time and geographical location, as well as Biblical texts.

According to forensic anthropologists, it is much more likely that Jesus looked something like this. I’ve come to realize that the Jesus that was introduced to me was created in the image of the colonizers.

Foundational to colonization is the idea of “other” who is less-than, while the colonizers’ ideas, values, person and accomplishments are superior. This superiority wasn’t just limited to how individual Europeans acted, they created doctrines, laws and edicts that guided how they were to view and treat whoever and whatever they encountered on their journeys.

This colonial Christianity narrative informed an entire worldview, which in turn, empowered the colonizers to define what right and real Christianity was. Everything outside the colonizers’ values, perceptions and norms was dangerous, unChristian and unsound.

As a black Christian woman, I began to grapple with this colonial Christian narrative and wrestled with what or who this whitened Jesus would say I was created for. In the gaze of the colonial Jesus, my options were limited to either the Mammy, the Jezebel or the violently angry and thuggish black woman. These false portrayals of black womanhood say that I am created for the purpose of being the “other” and for suffering. Instead I’ve discovered a counter narrative that says I am created with the potential to run for president, like Shirley Chilsom; or be a poet who uses her words and voice to speak for justice and liberation like Audre Lorde; or an entrepreneur and political activist that creates sustainable and empowering systems to feed her community like Fannie Lou Hammer. The image Jesus is cast in, whether His true Middle Eastern identity or the white European colonizer, informs my value and purpose as a Christian black women in a racialized world.

In my growing commitment to reclaim my faith from the grips of the colonial Christian narrative, I began a journey of decolonizing my Christianity. This journey was a commitment to bring all of myself before the Creator: my racial identity, my culture, my sexuality and my personality.

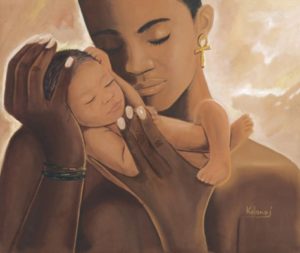

It was a practice of unlearning the narratives of who White colonial Christianity says that I am and learning to trust that the Creator looks at me, Her creation, and says “It is good.”

Reclaiming my faith is not only a mental exercise, it also includes reclaiming and embracing other areas of my life and developing practices like:

- Eating foods that both nourish my body and soul (the types of food that celebrate my cultural heritage)

- Loving and caring for my black body, embracing the hair that grows out of my head as good and wonderful even if it makes white people feel uncomfortable.

- Listening to the wisdom of sisters and elder mothers in the faith and ensuring that those who shape my faith are grounded in a theology of liberation (i.e.: womanist, mujerista theologians, Black theology, Black Radical Christians group, POC sisters who are keeping it real)

- Exploring my cultural faith lineage which includes:

- Culturally affirming styles of worship, playing my spirit instrument in worship (the drums: djembe, cajon, congas)

- Adapting the ways I talk about God (She, MoMMA, Nurturer, Defender, Creator)

- Re-connecting to indigenous practices (deep connection and understanding of the spiritual world, finding meaning in community and connection to the earth)

- Connecting with a People of Color / Queer People of Color community that is exploring what it means to reclaim our faith traditions, spiritual lineage and the intersections of mysticism and activism through the Mystic Soul Project & Conference

So, what does decolonizing Christianity have to do with justice? How does my personal story of reclaiming my faith intersect with yours within the Body of Christ? When we allow the narrative of White colonial Christianity to go unquestioned and unchecked, it aborts our capacity to experience the fullness of Shalom. Our ability to vision for justice is limited at best and ineffective at worst. Committing together to decolonize Christianity as an act of communal repentance clears the way for us to listen and respond to the prophetic voices and visions for building the Beloved Community. There are no shortcuts to doing this work. Don’t waste your time looking for an undo button, because there is no way to undo our shared past; no amount of pretending or wishing away is going to make things better. Instead, we must do the hard work of exploring, repenting and turning away from the narratives of White colonial Christianity. This is a permanent part of our story that is dangerous to overlook or underestimate.