At the Mennonite Church USA convention in Orlando in July, planners tried something new. Something they called MennoTalks. Not quite TED and not exactly Pecha Kucha, MennoTalks explored a different topic each day, featuring speakers from diverse perspectives. Topics included Celebrating Women (Wednesday); Race, Religion and Justice (Thursday); and Local and Global Peacemaking (Friday). Over the next several weeks, we’ll be featuring a series of posts based on the MennoTalk presentations in Orlando.

Nathan Grieser lives in Lancaster city, Pennsylvania, with his wife Kate and daughters Ivy and Juniper. He currently serves as director of The Shalom Project, an Anabaptist-founded voluntary service program. Nathan enjoys writing and playing music, bicycle commuting, gardening and woodworking. He is passionate about living simply and sustainably, connecting with people on the margins and creatively participating in God’s work of peace and restoration. Nathan’s MennoTalk was categorized under the topic Local and Global Peacemaking.

In Luke 9, Jesus calls his disciples together and sends them out to spread the Good News and heal the sick but with a twist. Rather than carrying their own food, money or clothes, they are to rely on the people with whom they come into contact in the towns they visit. Jesus sends the disciples out as vulnerable peacemakers.

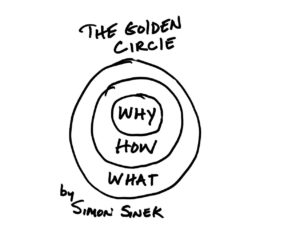

Author and consultant Simon Sinek created a model to help organizations think about their mission, and I find it helpful as we think about our calling to seek peace. The core of our calling, the “Why,” centers on the way of Jesus. The “What” part of the circle contains all the specific things we do to seek peace, in our homes, neighborhoods or across the world. Today I’m inviting us to examine our “How”: the way we go about translating our motivation to seek peace (why), into the specific things we do (what). Informed by the way Jesus sends his disciples in Luke 9, I believe we are called to seek peace vulnerably, mutually, relationally. That’s our “How.”

Author and consultant Simon Sinek created a model to help organizations think about their mission, and I find it helpful as we think about our calling to seek peace. The core of our calling, the “Why,” centers on the way of Jesus. The “What” part of the circle contains all the specific things we do to seek peace, in our homes, neighborhoods or across the world. Today I’m inviting us to examine our “How”: the way we go about translating our motivation to seek peace (why), into the specific things we do (what). Informed by the way Jesus sends his disciples in Luke 9, I believe we are called to seek peace vulnerably, mutually, relationally. That’s our “How.”

Like the disciples, we are invited to offer what we have in our pursuit of peace, and we are invited to receive from the very people we are sent to. The disciples carried the gift of Good News but also relied on people in the towns they visited for food and shelter. Going with a gift to offer and opening ourselves to receiving gifts from others, is the way of vulnerable peacemaking. Practicing vulnerable peacemaking can be a safeguard against doing violence to others. Vulnerable peacemaking invites us to see people, in their beauty and complexity, rather than projects that need fixing. I think Jesus sent his disciples out vulnerably so that they could discover gifts in others.

So what does vulnerable peacemaking look like? First, it involves a desire for mutual transformation.

This means that my core desire as a peacemaker is for both you and me to grow in our understanding, awareness, and love of God and one another. Like the disciples, I share my gifts and learn to rely on you and your gifts.

In 2014, my wife Kate was pregnant with our daughter Ivy. About that same time, our friends Jonathan and Karina told us excitedly that they were also expecting a baby. Jonathan and Karina were teenagers; their relationship was young, and they were experiencing challenges related to living in poverty. Kate and I reacted to their news with concern rather than joy. Jonathan and Karina’s son was born several weeks before Ivy. Jonathan gave us lots of good advice about the birthing process when we visited them in the hospital. He told us which foods we should eat at the hospital. He explained the pros and cons of circumcision, just in case Kate and I had a boy. He honestly helped us feel more prepared for Ivy’s birth.

I like to think Kate and I have extended peace to Jonathan and Karina. We walked together through pregnancy, and I ended up officiating their wedding ceremony. They changed me. They have dismantled my assumptions about them, as they care well for each other and do the hard work of being a young family. This, for me, is a story of mutual transformation.

Second, vulnerable peacemaking asks that we take relationship-oriented risks, building relationships with those who are different from us. Those of us with much privilege must be willing to move into marginal spaces, even if they are uncomfortable or disorienting, motivated by a deep care for the people who occupy those spaces and a desire to see the world through their eyes.

Building relationships with those who are different from us may risk our own identity, social standing or comfort. Jesus asked his disciples to travel to unknown places and to rely on the people they encountered along the way. He asked them to take this risk, I believe, so that they had the chance to form deep and authentic relationships with people.

Ellie recently finished a year with The Shalom Project, the voluntary service program that I direct. She spent her year working at a non-profit that does tutoring and literacy work in one of the more challenged neighborhoods in Lancaster City. Ellie spent her year without a car, instead relying on her funky folding bike to get to and from work. The risk of riding her bike made Ellie more vulnerable than in a car, and she had some negative experiences. But she was also able to trade hellos with her students when she saw them out and about. She noticed things about the neighborhood that she would not have noticed in a car, like how lack of investment has led to poor roads, lack of streetlights and food deserts.

Ellie chose to continue working and investing in the neighborhood after finishing her year with The Shalom Project. The risks she has taken have led to deep and trusting relationships with students whose backgrounds are very different from Ellie’s. Through her vulnerable risk-taking, Ellie is a more effective agent of God’s shalom in that neighborhood.

Third, vulnerable peacemaking asks that we define ourselves in relation to others, in community, rather than seeing ourselves as islands. This means that we hold our desires and vision alongside that of the other person or group with whom we are interacting, that we let the process and outcome of our work be shaped by all parties involved.

At its most authentic, defining ourselves in relation to others means that our desires and goals are shared, co-owned with the other person or people, as opposed to seeking only self-serving goals or imposing our goals on others. Our efforts are amplified because they are shared, and we are able to seek peace and transformation with far less risk of doing harm to the other person or people.

So I believe that our “How,” the way we go about seeking peace, is healthiest when it is done vulnerably, by seeking mutual transformation, taking relationship-oriented risks, and defining ourselves in relation to others. This way of functioning has the power to grow us and others in love of God, neighbor and self, as Jesus teaches in the Greatest Commandment.

Vulnerable peacemaking grows our love of God as we discover God’s presence and image in and through other people, expanding our concept of who God is. It grows our love of neighbor as we humanize others, moving beyond stereotypes and assumptions. We end up examining our biases and being formed more fully into the people God created us to be, a process that shapes love of self.

The amazing thing is that this growth is all intertwined: as we grow in love of God, we see God more fully in our neighbor and ourselves. When we grow in love of neighbor, Jesus reminds us that we are, in fact, growing in love of God. When we love ourselves more fully, we are able to foster healthy, authentic relationships with our neighbors. Functioning vulnerably as we seek peace invites us into the process of mutual transformation, relationship-oriented risk taking, and defining ourselves in relation to others. Ultimately, I believe, this way of being grows us and others in our love for God, neighbor, and self. Like Jesus’ disciples, may we be given the courage to move vulnerably as we seek peace.