Katerina Friesen is a recent graduate of Anabaptist Mennonite Biblical Seminary, Elkhart, Indiana. She is a writer and community builder, and currently serves as the interim pastor of Belmont Neighborhood Fellowship in Elkhart. Here she is pictured standing near the site at the Standing Rock encampment where direct action has been taking place. This post originally appeared on The Mennonite blog on Oct. 10, Indigenous People’s Day. Photo by Maria Thomas.

Katerina Friesen is a recent graduate of Anabaptist Mennonite Biblical Seminary, Elkhart, Indiana. She is a writer and community builder, and currently serves as the interim pastor of Belmont Neighborhood Fellowship in Elkhart. Here she is pictured standing near the site at the Standing Rock encampment where direct action has been taking place. This post originally appeared on The Mennonite blog on Oct. 10, Indigenous People’s Day. Photo by Maria Thomas.

The largest gathering of Native American tribes in over a century is happening near Cannonball, North Dakota, about a mile from the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation. Tribes that were once divided are finding reconciliation and unity in a movement of nonviolent resistance to protect the sacred lands and waters of the Lakota Sioux.

From Sept. 16-23, I traveled there with a delegation of Mennonites from the Dismantling the Doctrine of Discovery Coalition to show support and solidarity with the thousands of people resisting the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL), slated to carry over 450,000 barrels of crude oil per day from the Bakken shale of North Dakota to refineries in Illinois, over 1,100 miles. Our delegation included Anita Amstutz, John Stoesz, Ken Gingerich, Maria Thomas, and I, stayed at the Sacred Stone Camp, the first of the three main camps where between 5,000–7,000 people were estimated to have camped during the week we visited.

The Standing Rock Sioux tribe and their supporters call themselves “water protectors, not protestors,” and their rallying cry is Mni Wiconi! (Lakota for “water is life!”). During their gathering, they have been pepper-sprayed and attacked by dogs from DAPL private security and denied drinking water and sanitation from the state of North Dakota as they put their lives on the line for the Missouri River.

Some Mennonites must have been at Sacred Stone Camp before us! Among the flags raised there was this “Pray for Peace, Act for Peace” banner. Photo credit: Ken Gingerich

In a classic case of environmental racism, DAPL was rerouted from its original path just north of Bismarck (about 90% white) to cross the river less than a mile from the Standing Rock Reservation. The people camped there view their battle against the “Black Snake” of the pipeline as a spiritual, as well as physical, struggle and emphasize the integration of prayer and nonviolent direct action. Their goal is to stop construction by the Energy Transfer corporation on the DAPL for three main reasons:

- You can’t drink oil. The planned pipeline would cross under the Missouri River less than a mile from the Standing Rock Reservation, threatening their source of drinking water if or when an oil spill happens. The people we met emphasized that they are protecting the water not only for their tribe, but for everyone downstream as well. The pipeline is slated to cross rivers and waterways over 200 times on its route south, heightening the chances of a disastrous spill as it passes through critical wildlife habitat and farmland in North Dakota, South Dakota, Iowa and Illinois. Though oil company executives claim pipelines are a safe way to transport oil, analysis shows there have been an average of 300 oil spills per year for the last 30 years from the nation’s oil and gas pipelines.

- Climate change. Burning the crude oil transported by pipelines such as DAPL will worsen climate change, pushing us further toward catastrophe. Last month, scientists announced we have permanently passed 400 ppm of Carbon Dioxide in the atmosphere, 50 ppm above the threshold considered safe. Indigenous Peoples are among the most vulnerable populations who suffer the impact of non-native, carbon-energy based lifestyles. And they are also on the frontlines of the movement against climate change toward a more just, renewable way of living as part of creation rather than separate from it.

- Inadequate consultation. The Standing Rock Sioux tribe was not properly consulted about the pipeline’s cultural and environmental impacts. First, DAPL did not adequately survey the historically and culturally significant area near the Missouri River where the pipeline will cross. DAPL construction has already bulldozed sacred sites, including an area where the tribe recently documented an important burial site. Second, the Army Corps of Engineers fast-tracked the pipeline permitting process through a review loophole (known as Nationwide Permit 12) designed for small projects, rather than subjecting it to sufficient environmental review. Farmers and landowners in Iowa are also joining in a legal battle, since their land was seized through eminent domain for the same pipeline, considered by the state to be a public good. Pipeline construction on Army Corps of Engineers land 20 miles of both sides of the Missouri River was halted after a rather remarkable joint statement issued by the Department of Justice, the Department of the Army, and the Department of the Interior on Sept. 9th. The case is currently in a federal appeals court awaiting a decision on an injunction filed by the tribe’s lawyers.

In spite of the reasons outlined above to stop the pipeline, the courts may determine that the DAPL is completely legal.

Yet the abolition movement to end slavery, the South African apartheid struggle, and the U.S. civil rights movement have shown that what is legal is not necessarily moral.

Because of the Doctrine of Discovery, Western legal systems have continued to favor the extraction of resources on Indigenous lands to benefit the formerly Christian, European colonial powers that “discovered” those lands. Today it is not just governments dispossessing people of their land, but multi-national corporations and banks set to make billions of dollars.

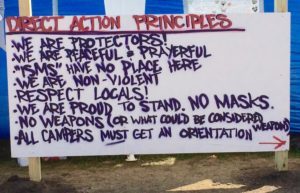

Sign at the Oceti Sakowin Camp. Photo credit: Ken Gingerich

The theft of land and resources that was justified in the name of Christianity and civilization is only one aspect of the Doctrine of Discovery. It was also a cultural and spiritual conquest of Indigenous identity. Native languages and religious practices were banned, Indian residential schools run by churches were tools of systematic assimilation, and the buried remains of Native peoples’ ancestors were dug up and shipped to museums for display. In the wake of this traumatic history, the movement represented at Standing Rock is resisting not only land colonization, but the colonization of Indigenous culture and spirit. During our time at Standing Rock, we observed an incredible swell of dignity and pride in Indigenous culture and identity, shown in dances and regalia, a school teaching Lakota language to children, and daily practices of ceremony and prayer. A young college student I met became emotional as he shared how his beloved grandfather let him borrow his tipi and showed him how to use it so that he could camp in a traditional way through the winter at Standing Rock. Another young man described the ways his participation in sweat lodge ceremonies has helped him recover a sense of belonging and heal from past wounds.

A momentous cultural-spiritual revival is happening at Standing Rock. The people are reclaiming what was stolen, outlawed, and degraded for so long, and the healing energy is palpable.

Can that healing extend to Mennonites, particularly those of European descent? We all need healing, since colonization damages not only Indigenous Peoples and other people of color, but also those of us who inherit the benefits of conquest. When we returned from our time at Standing Rock, our all-white delegation reflected on the ways that solidarity with Standing Rock offered us opportunities to decolonize our own hearts and minds.

The Doctrine of Discovery grew out of a severe distortion of the gospel of God’s love for creation. It contributed to a worldview that sees land and water as resources to extract rather than gifts of the Creator; as obstacles to progress and development rather than relations we are bound to protect and honor. As our delegation spent time talking, eating, praying and camping alongside Indigenous sisters and brothers, our eyes were increasingly opened to a different way of seeing the world as sacred and interconnected. There are paths within our Judeo-Christian tradition and scriptures to both remember this way that leads to life and to repent of the ways of death that inevitably destroy us all.

Before we left, our delegation gathered at the river to pray for the waters and for the water protectors willing to risk so much. We collected some of the water to carry home with us to remember our time and our commitment to continue the work of healing. The Sunday I returned to Elkhart, I poured the waters of the Cannonball River (which flows into the Missouri) together with the waters of the Elkhart River in a prayer of unity. As our separate waters flow together and become one, may we also be unified in love for one another and for all land and waters, heeding the example and call of Indigenous Peoples to protect sacred life under threat everywhere.

Additional resources:

- Check out the first episode of the Peace Lab podcast, featuring Erica Littlewolf reflecting on the Doctrine of Discovery and the Standing Rock Sioux encampment.

- Read a statement of support to the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe from Michelle Armster, MCC Central States Executive Director (August 31, 2016).