Chris Hoover Seidel is a spiritual director and Reiki practitioner and is on staff at the Center for Justice and Peacebuilding at Eastern Mennonite University. She is a graduate of Lancaster Theological Seminary and attends Community Mennonite Church in Harrisonburg, Virginia, where she lives with her family. Her work, “Sophia at the Crossroads: Dismantling Patriarchy in the Church through the Biblical Goddess,” will be published next year in I’ve got the power, a collection of essays based on presentations at the 2016 Women Doing Theology Conference hosted by the Women in Leadership Project. To learn more about Chris’ work, visit www.soulence.space.

Chris Hoover Seidel is a spiritual director and Reiki practitioner and is on staff at the Center for Justice and Peacebuilding at Eastern Mennonite University. She is a graduate of Lancaster Theological Seminary and attends Community Mennonite Church in Harrisonburg, Virginia, where she lives with her family. Her work, “Sophia at the Crossroads: Dismantling Patriarchy in the Church through the Biblical Goddess,” will be published next year in I’ve got the power, a collection of essays based on presentations at the 2016 Women Doing Theology Conference hosted by the Women in Leadership Project. To learn more about Chris’ work, visit www.soulence.space.

Before I sat down to write this, I went for a run. Before that, I danced. And before that, I sobbed. These particular actions were a domino effect response to my daughter naming a specific negative image of her body. She’s eight.

To feel as if I’m losing a battle I’ve been fighting since before she was born is not surprising. But that doesn’t lessen the devastation. And it all feels especially poignant since I’ve been on a journey of reclaiming my own body.

Miraculously, beyond my ability to physically numb out, my body sent me a message this past year. From somewhere beyond words and logic, I became aware that if I didn’t pursue a deeper level of physical healing, then I would risk severe illness. In many ways, I’m a perfectly healthy person. On the other hand, I’ve had an immense amount of trauma stored in my body since before I can remember, and my body is wise enough to know it needs to be dealt with.

Listening to my body was the first step. I then enrolled in the Strategies for Trauma Awareness and Resilience (STAR) class through the Center for Justice and Peacebuilding to learn more about trauma and resilience. I was introduced to Trauma Release Exercises (TRE), and began to see a massage therapist regularly in order to target specific problem areas. All of this led to me understanding that the root of my issues was literally tied up in my psoas muscle, where most of our “stuck” trauma is stored. One entire side of my psoas wouldn’t move. My massage therapist described it as “angry.” The moment I heard that, I experienced an unprecedented rush of compassion for my body. Then I began to really feel it and the pain it was carrying. And that was perhaps the most devastating realization — that I wasn’t feeling my body and its pain. I was separate from her. We were a living binary, day in and day out. We had been for decades.

In May 2016, I graduated from seminary. That fall, I presented my capstone project at the Mennonite Women Doing Theology Conference. The theme of the project was leveraging a biblical goddess to re-image the Divine for the sake of dismantling patriarchy in the church and building justice that included all people. This work was an important part of my journey of healing, because the bible had become a symbol of trauma, as it was used against me from the time I was a little girl attending church. The bible was used to suppress my body, sabotage my agency and force me to sacrifice my own self-love. Doing the work of becoming an empowered reader of the bible was vital, but the problem of my own disembodiment remained, as much as I sought to uncover a better way.

Historically, a problem of white feminism has been that we are too often satisfied with small shifts in patriarchy based on theoretical work within systems defined by white supremacist, capitalist patriarchy. This whiteness fuels our disembodiment because it is invested in oppressing bodies — black, brown, female, queer, and the brown, feminine body that is the earth. Womanists, people of color and the queer community call us to the embodied realities of justice work by interrogating our white patriarchal cultural norms and directing us to see how justice work intersects in all areas of life.

In order to respond, we need to name the inability of the church — our Mennonite churches — to deal with bodies — particularly those that do not swim in the river of masculinity in which we have baptized our own image of God.

And yet, the whole point of the church is to be a body. But we are struggling with our own numbing. We hear the voices of marginalized groups calling, and we find ways to numb ourselves to that pain within our body. Numbing is silencing. And it has led to disease. Eventually it will lead to irrelevance.

This summer I enrolled my daughter in an eco-feminist camp, because I knew I needed to compensate for the work the church wasn’t doing in cultivating the divinity and power of her female body. Simply stated, I don’t trust the church to do this work — even churches that don’t overtly sabotage women and girls. If the church isn’t actively oppressing women’s bodies, then it’s usually just silent on the topic. Layer on all the patriarchy still prevalent in our worship, and it feels like a losing battle.

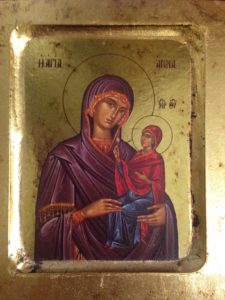

I purchased this icon in the Old City (Jerusalem), Palestine. It’s of St. Anne and St. Mary, a mother and daughter pair.

A few weeks ago, a male Mennonite pastor was invited to speak at our church retreat on the theme of Mary. With great authenticity, he proclaimed the powerfully prophetic words I had been waiting for a full decade to hear from the pulpit.

He said, “If we want to understand the gospel, I think we need to start with a woman’s body.” Tears of relief and gratitude streamed down my face. I couldn’t believe what I was hearing!

And yet, I wondered why it took a man, as a visiting guest speaker on a special weekend, to be the one to say this. I wondered if the power of this reflection would stay behind at our lovely retreat campgrounds or if Mary would be invited to accompany us back to town to be with us every Sunday. That is to ask ourselves if we’re willing to continue to honor the sacredness of women’s bodies in the church — mine, my daughter’s, single, divorced, queer, brown and black — in order to become a more embodied church, not numbed to those who are crying out in pain.

My journey of healing has led me to some deep integrative healing work. Within the intentional space of that work, I have opened myself up to feel anything and everything my body needs to express. That has included trauma. Recently I got in touch with some of that trauma, and my body went into a fight or flight response — my heart started racing, my body shook and I cried in pain through streams of tears. At that moment, I was aware of what the disembodied part of me needed to do — stand in solidarity with myself. My disconnected self stood alongside of my body feeling all of the pain, and I promised to bear witness, to stay present and to be there when she came through — not unlike the women at the crucifixion and tomb of Jesus. And she did come through that day. She continues to come back to life, and the beautiful thing is that I’m no longer journeying alongside her. I am her. Together we are defying the imposed binary of body and mind through deep spiritual work.

The Divine wisdom I experience through her has become my inner compass. It is the very real channel of Divine love mixed with the humus of my female body, further defying the most devastating binary Christians could embrace — divinity and humanity. Mary knew that. She carried the reality of divine presence within her body.