Jason Kauffman is director of Archives and Records Management for Mennonite Church USA

In 1995, the Mennonite Environmental Task Force (METF) organized a “Creation Summit” in Camp Lake, Wisconsin, that brought together farmers, educators, mission workers, and students from across North America. While the goal of the conference was to develop an “Anabaptist theology of environmentalism,” many in attendance had a hard time locating a concern for the environment within the Anabaptist theological tradition. Theologian Walter Klaassen concluded that “despite a commitment to nonviolence, Mennonites … have done no thinking about nonviolence toward the Earth and ‘are by no means in the Christian front ranks of creation care.’” Mennonite scholar Calvin Redekop echoed Klaassen, claiming “there is absolutely no reference to the preservation of the earth in Mennonite theology.”

In a book published in 2000 as a result of the summit, many contributors pointed to Anabaptist traditions — including nonviolence, simple living, stewardship, and rural, agricultural lifestyle — as building blocks for the construction of an environmental ethic centered on the responsible care of God’s creation.

However, other contributors noted that these Mennonite traditions and historic “closeness to the land” have not always translated into concern for the environment.

These references to Anabaptist traditions touch on historical dimensions of the Mennonite experience with the environment that, for the most part, went unexamined in the book. I would suggest that a useful step for building an Anabaptist theology of creation would be to spend more time exploring how and why Mennonite attitudes about and interactions with the environment have changed over time.

What can the archival record tell us about these historical relationships? Given Mennonites’ rural past, one logical lens to examine Mennonite interactions with the environment is through the study of farming and agriculture. In general, however, Mennonite archives have done a much better job documenting the voices of institutional and thought leaders than they have for the stories of the Mennonite “rank and file” — farmers, business owners, agricultural workers, and others — whose livelihoods depended more directly upon the fruits of nature. Fortunately, historians are starting to examine agriculture as a central component of Mennonite environmental history, not only in North America, but in Mennonite communities around the world. An upcoming conference on the history of the Mennonite Central Committee will provide further opportunities to illuminate the environmental dimensions of Mennonite relief and development work abroad.

1947. Goshen, Indiana. Audobon Club at Goshen College. Dr. Alta Schrock, sponsor. Citation: Mennonite Community Photograph Collection, 1947-1953. Goshen College. HM4-134 Box 2 Photo 305-17. Mennonite Church USA Archives – Goshen. Goshen, Indiana.

Another potential source for examining Mennonite environmental history is through the lives of scientists, many of whom served as educators at institutions of higher learning.

For example, before embarking on her entrepreneurial career, Alta Schrock taught biology at Goshen College from 1946-1957. A person of unbounded intellectual curiosity, as a youth Schrock “embarked on a systematic study of the flora and fauna that existed within a 15-mile radius of her home” and built a Thoreau-esque cabin in the woods to observe and write about nature. She earned a Ph.D. in biology from the University of Pittsburgh in 1944.

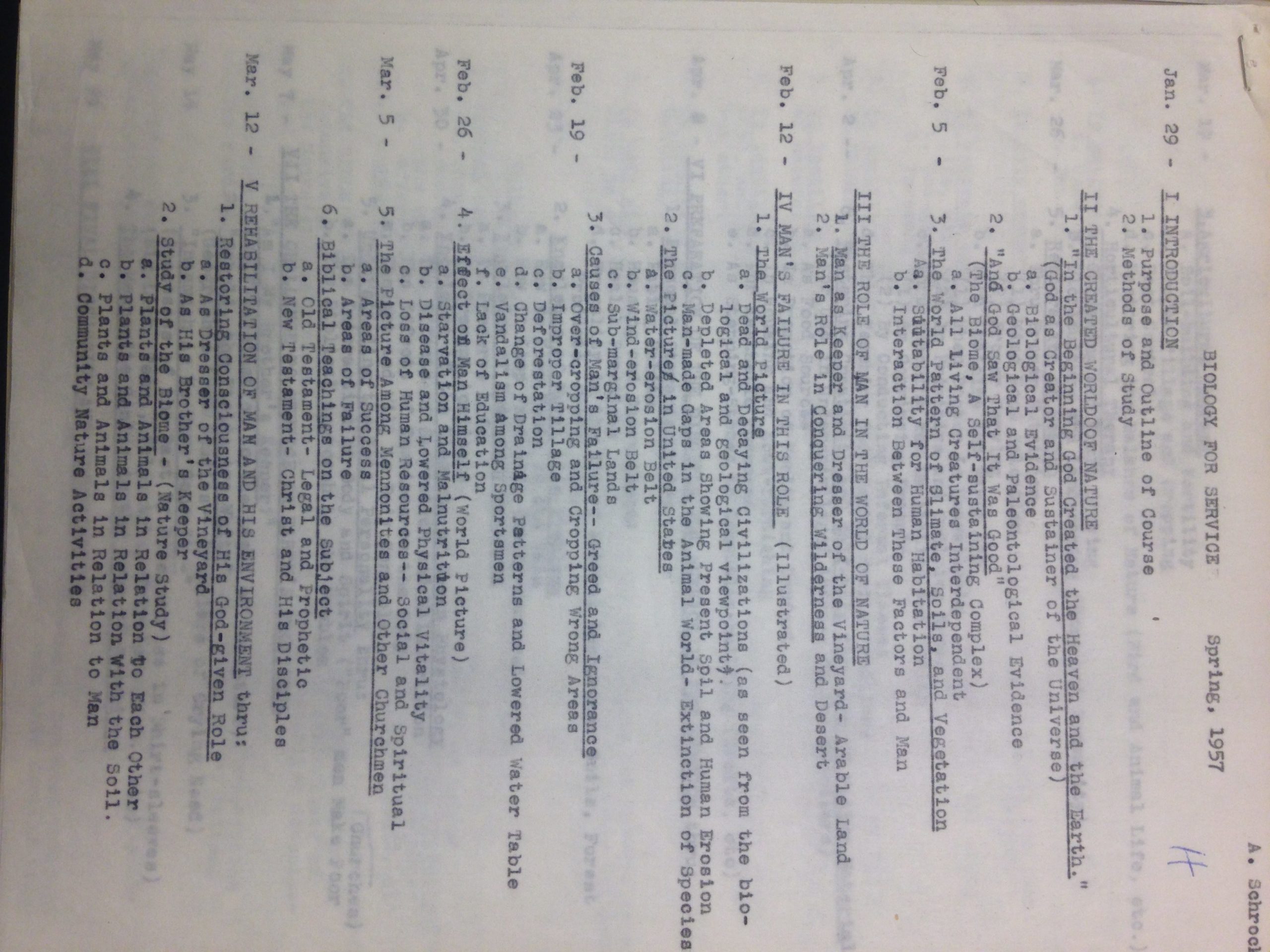

At Goshen, Schrock taught biology and was a faculty sponsor for the college’s Audubon Society chapter. In 1957 she taught a course entitled “Biology for Service,” which she developed for a new (and short-lived) curriculum to provide practical agricultural and business education for Mennonite farmers. The course was designed to place man’s relationship to the natural world in both historical and Biblical context. Objectives for the course included motivating students “toward a purposeful and rigorous stewardship in all areas of life, with accent on stewardship of … God-given natural resources” and “to help give practical implementation to the way of love and non-violence.”

“Biology for Service” syllabus, Alta Schrock, Spring 1957, Goshen College

Schrock’s syllabus provides remarkable insight into her lived theology of creation, one informed by her own experiences in nature, her education and her Mennonite upbringing. She developed the syllabus during a time when the American scientific community and broader society was only beginning to grasp the interdependence of humans and the natural environment. In the process, she anticipated (by several decades) many of the same questions — on faith and the environment — which conference-goers discussed at the 1995 Creation Summit. Indeed, it is no coincidence that the majority of those who enrolled in her course were seminary students.

In April 2017, Anabaptist Mennonite Biblical Seminary will host its third “Rooted and Grounded” conference devoted to theological discussion on land and Christian discipleship. It comes at a time when the Mennonite community in North America is as urban as it has ever been. Creation care thus poses challenging questions about our alienation from the land and the responsibility we share for the present environmental crisis. Yet, as Rebecca Horner Shenton argues in a recent essay, this growing and widespread interest in creation care should not lead us to assume that environmentalist thought among Mennonites is only a recent phenomenon.