Jason Kauffman is director of Archives and Records Management for Mennonite Church USA. He offers this snapshot into a church planting movement in Mennonite history as we Learn, Pray, Join for Peace Church Planting.

Jason Kauffman is director of Archives and Records Management for Mennonite Church USA. He offers this snapshot into a church planting movement in Mennonite history as we Learn, Pray, Join for Peace Church Planting.

On April 12, 1978, Mennonite Board of Missions (MBM) appointed Edward Taylor as associate secretary of Home Missions. Taylor was a newcomer to the Mennonite world. Born in Dublin, Georgia, he moved to Cleveland, Ohio, with his family as a young child. While he worked for most of his adult life as a corporate production manager in Cleveland, he was also an active church and community leader. In addition to coursework in urban studies at Case Western Reserve University, Taylor graduated from Ashland Theological Seminary in 1979 at the age of 56.

His introduction to Mennonites came later in life through Vern Miller, pastor at Lee Heights Community Church, who impressed Taylor with his commitment to interracial and ecumenical relationship building. Taylor began attending Lee Heights in 1973 and, in 1976, he and Miller established Cleveland Heights Mennonite Church. Less than two years later, the Black Council of the Mennonite Church identified Taylor as the preferred candidate to lead the new “urban thrust” mandated by delegates at the 1977 General Assembly.[1]

“Planting a Church in a People Garden,” Mennonite Board of Missions, 1979. Provided by Mennonite Church USA Archives.

Shortly after Taylor began, MBM began to publicize the urban ministry initiative to the broader church. In 1979, MBM produced Caring Project materials for Mennonite congregations entitled “Planting a Church in a People Garden.” Designed for use in summer Bible school projects, the materials focused on the story of Jonah and his call to serve the city of Ninevah. Joel Kauffmann and Phil Yoder also coproduced a film featuring the voices of church planters working to “cultivate [God’s] garden” in cities across the United States.[2] Project offerings supported a new church planting effort in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, between MBM, Allegheny Mennonite Conference, and Pittsburgh-area Mennonites.

Taylor saw the Pittsburgh project as an opportunity to develop a “model of cooperation for future Mennonite church-planting.” With financial support from MBM, the Pittsburgh Mennonite Council formed in 1978 to coordinate existing Mennonite ministries in the city, including an emerging effort to plant a biracial church in the Manchester neighborhood. After over a year of planning, however, the council abandoned the effort in January 1981, citing resistance from community leaders and the inability to secure a pastor.[3]

The Pittsburgh experience underscored several realities that challenged Taylor’s urban initiatives. Writing in July 1980, Taylor described his first two years with MBM as “an educational, interesting, many times perplexing, frustrating, and yet broadening experience.” Particularly frustrating was what he saw as unclear lines of authority between conferences, congregations, and MBM and the slow pace of institutional change. This resulted in a fragmented urban witness and slowed efforts to move forward with the urban ministry thrust.[4]

The Pittsburgh experience also showed Taylor the importance of leadership development for urban pastors, especially for people of color and those without formal theological education.

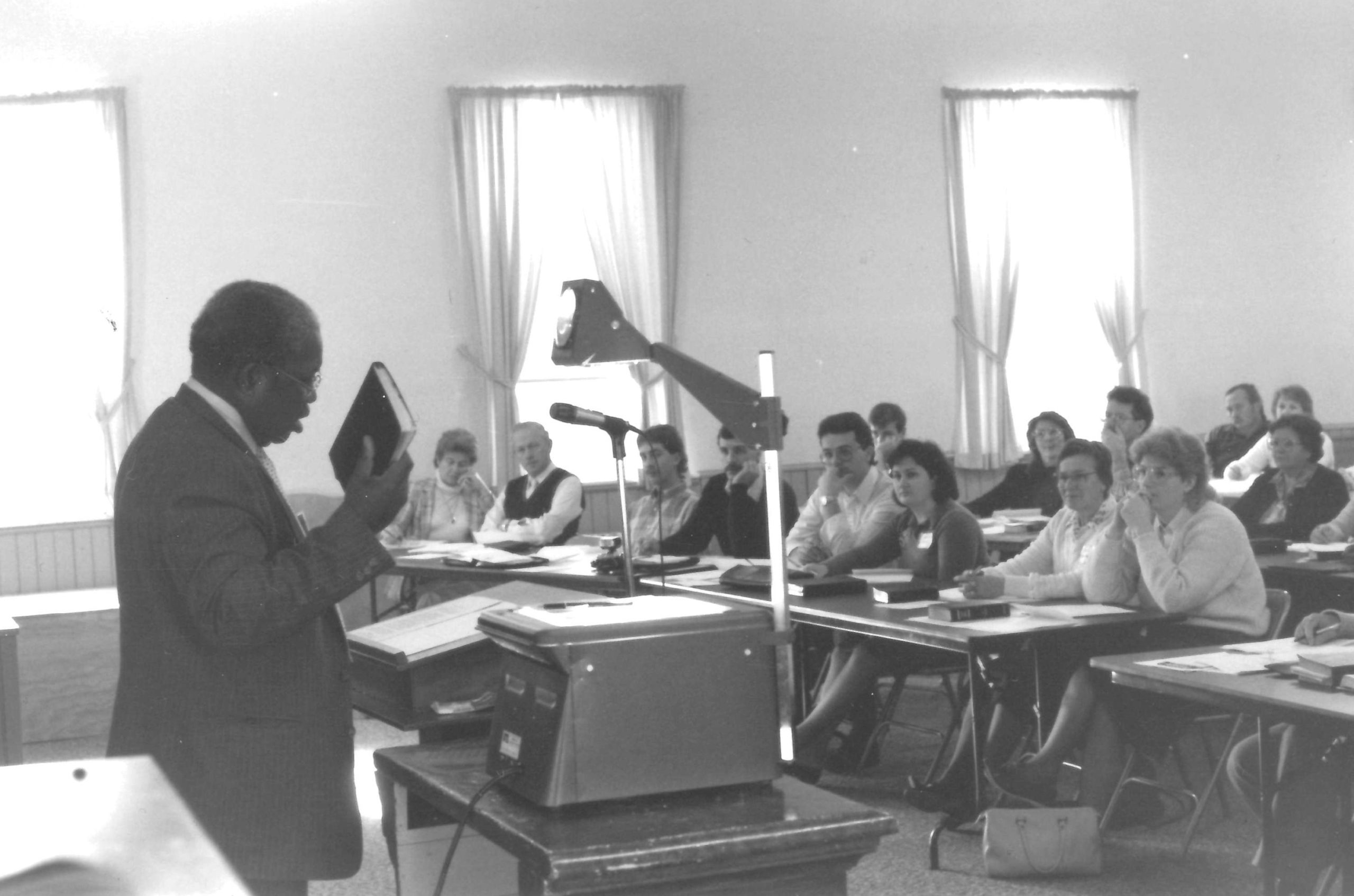

Ed Taylor leading a “friendship evangelism” seminar in 1986. Photo provided by Mennonite Church USA Archives.

In 1979, he developed a proposal for a leadership development center that would provide free training to people of color, Voluntary Service workers, and others interested in church planting. He believed that a systematic program of leadership development – focused on evangelism, intercultural awareness, and relationship building – was essential for successful church planting and growth.[5]

In the following years, Taylor continued in leadership positions at MBM, first as Director of Home Missions and later as Director of Church Development. In 1984, however, he cut back his time with MBM to focus more energy on church planting in Cleveland. While his plan for a leadership institute never materialized, Taylor continued to stress the need to train pastors for work in cities and led church planting and “friendship evangelism” workshops for MBM until his retirement in 1988.[6]

Taylor’s story provides an interesting window into the history of Mennonite church planting. As a church planter, Taylor knew what it took to build and sustain a local church. The challenge was to convince stakeholders at denominational, conference, and local levels to get on board with his plan. Taylor wanted less talking and more doing and grew frustrated with the seeming lack of commitment from the broader church. As MC USA embarks on its new Journey Forward process, it is worth taking stock of how far we have come since the urban thrust of the 1980s. How has our denomination changed in the last 40 years? What progress have we made toward helping new communities of faith to emerge and thrive? What do we still need to work on? How can we best work together to share Christ’s message of love to our friends and neighbors?

________________________________________________________________________

[1] Joel Kauffmann, “Edward C. Taylor: City Salesman,” Sent, 25:2 (April 1979), p. 2-3.

[2] Both the caring project materials and the film are located in the MC USA Archives in Elkhart, Indiana. See also, Joel Kauffmann, “Filming A People Garden,” Sent, 25:2 (April 1979), p. 8-11.

[3] More details are available in Pittsburgh Council Minutes, Mennonite Board of Missions Evangelism and Church Development Conference Correspondence and Subject Files, circa 1980-2015, IV-16-23, Box 2, MC USA Archives, Elkhart, Indiana.

[4] Taylor to Personnel Committee, July 15, 1980, MBM Evangelism and Church Development Data Files, Part 4, 1970-1980, IV-16-21.4, Box 3, Folder 10, MC USA Archives, Elkhart, Indiana. See also Taylor’s comments on racism and white Mennonite resistance to his leadership in Edward C. Taylor, “Being a Black Administrator in the Mennonite Church,” Festival Quarterly, Feb.-Apr. 1982, p. 7.

[5] Ibid. See also, MBM Home Ministries Division Minutes, 1964-1988, IV-16-01.

[6] The workshops were modeled after Art McPhee’s book, Friendship Evangelism: The Caring Way to Share Your Faith (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Zondervan, 1978).