A look at how the (Old) Mennonite Church addressed the crisis of decreasing youth involvement with innovative solutions and an emphasis on the value that young ideas offered.

This article was first published in the MC USA Archives News, Vol. 3, Issue 1.

Olivia Krall

Olivia Krall is the archives coordinator for MC USA. She strives to use the powerful history of the church to engage and inspire people. She graduated from Goshen College in 2023, with a Bachelor of Arts in history. Prior to joining the MC USA Executive Board staff, Olivia worked at the Elkhart County (Indiana) Historical Museum. Olivia attends Southside Fellowship, a congregation within the Central District Conference.

______________________________________

This article focuses on the (Old) Mennonite Church, which merged with the General Conference Mennonite Church in 2002 to form MC USA.

Throughout the history of the (Old) Mennonite Church, young people challenged, engaged and pushed the church in new directions.

In the 1920s, the Mennonite Church faced a problem – it needed to engage young people. In the post-World War I period, young adults who had survived those turbulent times felt the church had not done enough to support conscientious objectors or to promote peace in the post-war age. Youth and young adults also bristled against ideological differences, particularly as the Mennonite Church navigated a rise in fundamentalism.

In the 1920s, the Mennonite Church faced a problem – it needed to engage young people. In the post-World War I period, young adults who had survived those turbulent times felt the church had not done enough to support conscientious objectors or to promote peace in the post-war age. Youth and young adults also bristled against ideological differences, particularly as the Mennonite Church navigated a rise in fundamentalism.

Church leader Orie O. Miller commented in a letter that, of young Mennonites between 16 and 25, “large numbers of them are leaving and dropping out” of the church in the post-war period. In response, both institutional and independent organizations formed to address the  problem.

problem.

The first real call to the Mennonite Church to turn its attention to youth came from the creation of the Mennonite Youth Conference Movement. The first conference was held in 1919 in Clermont-en-Argonne in France by Mennonite relief workers. Frustrated with the church’s lack of support for their work and experiences in the war, the workers felt a need to convene as a generation to discuss their experiences as non-resistors and the future of the church.

The Young People’s Conference pressed the church to reform and expand its vision outward – to work on a broader level for peace, engage with other denominations, and to be more missional.  However, while members of the YPC intended for their movement to strengthen the church, some denominational church leaders did not perceive it this way, and YPC gatherings faced resistance.

However, while members of the YPC intended for their movement to strengthen the church, some denominational church leaders did not perceive it this way, and YPC gatherings faced resistance.

By 1923, YPC no longer existed. Attempts to work with the church had failed and many of the more progressive leaders left either for the General Conference Mennonite Church or other denominations. However, as Anna Showalter writes in her 2011 article about the YPC, eventually, though more slowly than youth leaders would have liked, the church carried out many of the reforms the YPC suggested.

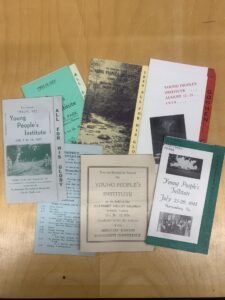

In 1924, in response to the YPC and recognizing the need to speak directly to youth, the Mennonite Church created a Young People’s Problems committee. By 1929, the church organized its own meetings for young adults, called the Young People’s Institute. The first meeting, held in Goshen, Indiana, was a five-day conference that offered Bible courses, worship time and a discussion-and-assembly period, during which young leaders could discuss issues facing the church and provide feedback.

In 1924, in response to the YPC and recognizing the need to speak directly to youth, the Mennonite Church created a Young People’s Problems committee. By 1929, the church organized its own meetings for young adults, called the Young People’s Institute. The first meeting, held in Goshen, Indiana, was a five-day conference that offered Bible courses, worship time and a discussion-and-assembly period, during which young leaders could discuss issues facing the church and provide feedback.

Soon these meetings spread across the denomination. In 1939, Orie Miller wrote in a letter to Bishop A.J. Metzler that the Institutes had served as useful for reaching disaffected youth from WWI and that the “Institute represents one logical outlet for that type of young people’s work and interest.”

These meetings proved to be powerful in encouraging youth to connect with the Mennonite faith and, during the beginnings of World War II, offered Mennonite youth an opportunity to discuss the tenets of their faith. A 1942 attendee of the Institute wrote of the experience, “I am thankful for an army of young men and women that are interested in the things of God.”

These meetings proved to be powerful in encouraging youth to connect with the Mennonite faith and, during the beginnings of World War II, offered Mennonite youth an opportunity to discuss the tenets of their faith. A 1942 attendee of the Institute wrote of the experience, “I am thankful for an army of young men and women that are interested in the things of God.”

The Institutes continued into the mid-1950s, when the proliferation of Mennonite camps and other youth programming, including Mennonite Youth Fellowship, filled the need for youth outreach. The crisis of youth leaving the church eventually led to innovative solutions and an emphasis on the value that young ideas and perspectives offered.

Citations

Archival Sources:

Laurelville Mennonite Church Center (Mt. Pleasant, PA) Records, 1930-2023. VII-24-04. Mennonite Church USA Archives. Elkhart, Indiana.

Young People’s Problems Committee Records, 1920-1954. I-03-06. Mennonite Church USA Archives. Elkhart, Indiana.

Jacob Conrad Meyer Papers, 1888-1968. HM1-044. Mennonite Church USA Archives. Elkhart, Indiana.

Secondary Sources:

Kauffman, Jason. “The Young People’s Conference Movement and the Church of the Future.” Anabaptist Historians, May 4, 2018. https://anabaptisthistorians.org/2018/05/04/the- young-peoples-conference-movement-and-the-church-of-the-future/.

Showalter, Anna. “The Mennonite Young People’s Conference Movement, 1919-1923: The Legacy of a (Failed?) Vision.” Mennonite Quarterly Review 85, no. 2 (April 2011): 181–218.

Do you want to read more stories like this? Read the Archives News, the new quarterly newsletter from the MC USA Archives, here.

Do you want to read more stories like this? Read the Archives News, the new quarterly newsletter from the MC USA Archives, here.

The MC USA Archives seeks to inspire people worldwide to follow Jesus Christ by engaging them with the historical record of Mennonite Christian discipleship. Help the Archives continue to share stories like this one by donating here.

Bonus for Archives supporters: We are pleased to provide our Archives supporters with an exclusive printed copy of our quarterly newsletter.