Brian Best of the Samaritans described red dots on a map representing the estimated 4,500-plus unidentified bodies found in Maricopa County, Arizona, who are believed to be immigrants. Photo by Wil LaVeist.

Wil LaVeist is the chief communication officer for Mennonite Church USA and the senior executive for advancement at Mennonite Mission Network.

A person’s name matters. A name can indicate whether you are family. For an immigrant, a name can determine acceptance.

From where our migrant learning tour group had gathered at the shelter in Tucson, I noticed a man with his son sifting through a rack of clothing. As we approached them, we learned they both shared the same name – Carl.

Carl and his family were preparing to resettle in Michigan. Like those European immigrants who, more than a century ago, fled home to settle in states like Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Missouri, they too had fled persecution in their homeland.

“There are no gangs there,” Carl explained passionately of his home country. “The government is the gang.”

I thought of the Mennonites who after the fall of Nazi Germany ending World War II, received help from Mennonite Central Committee to resettle in the United States.

At a different part of the migrant shelter, our group heard another wrenching story from a man named Orland. With his wife, Beth, and their 3-year-old daughter sitting beside him, Orland told of being shot five times. He pulled his shirt sleeves back from his forearms to reveal wounds. Beth lowered her head.

“We didn’t come here to do any damage,” Orland said. “We want to work.”

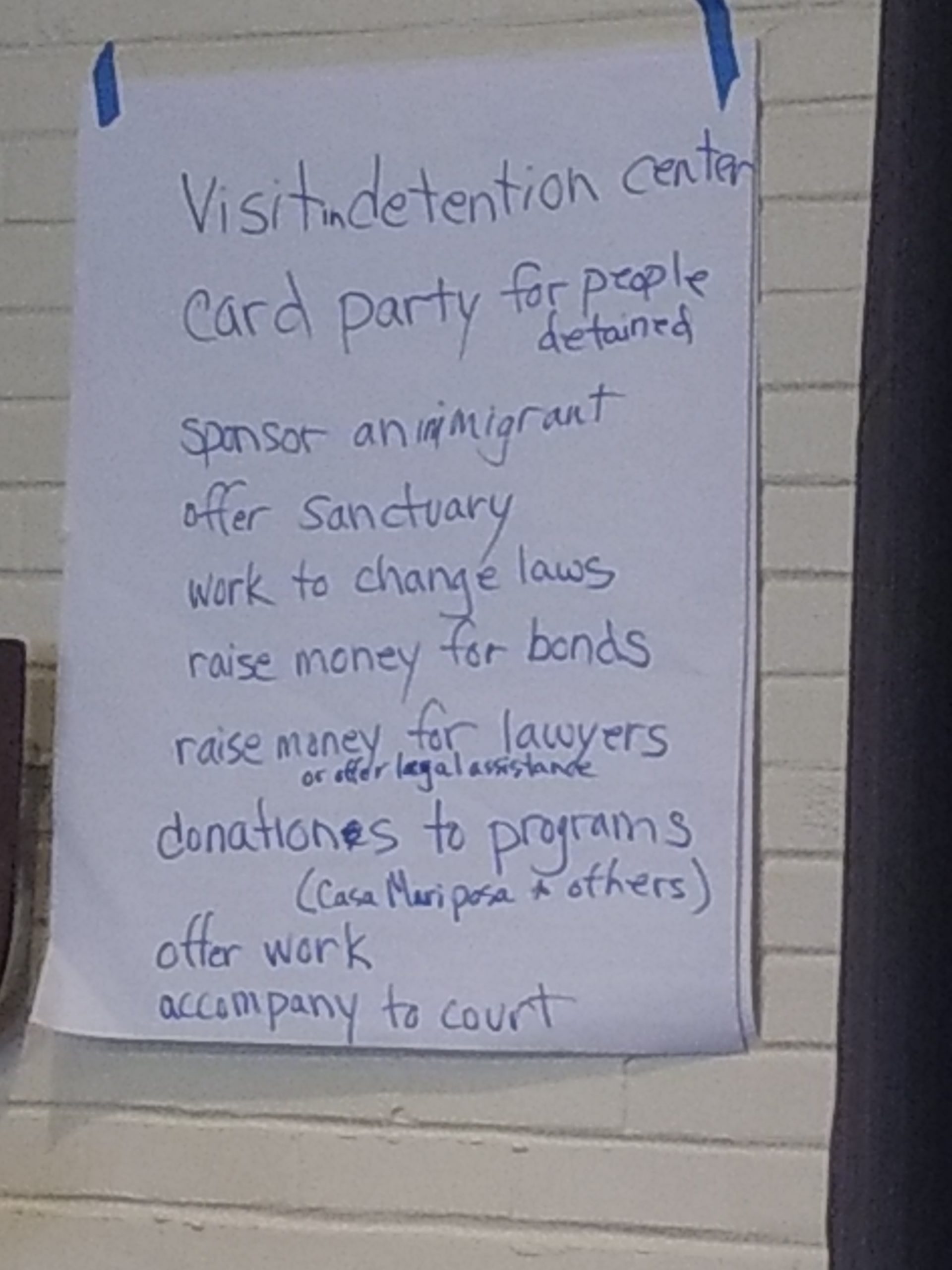

A handwritten sign posted inside Shalom Mennonite Fellowship in Tucson lists suggestions of how individuals and congregations can address the immigration crisis. Photo by Wil LaVeist.

I imagined his words being like those said by immigrants who were processed through Ellis Island in New York City beginning in the late 1800s. Those who found hope in words, “Give me your tired, your poor, Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free…,” words originally inscribed on the Statute of Liberty in 1903 to celebrate Black American slaves recently freed.

Work was all Rose wanted to do. Our group heard her story when we visited Shalom Mennonite Fellowship in Tucson, which hosted us. Rose said a friend back home duped her into traveling to the U.S. to work as a caretaker for an elderly person. Rose’s job in California was fine at first, but then her pay stopped. She was also abused, she said. When Rose tried to return home by plane, there was confusion and more lies, she said. With no way home, Rose explained to U.S. border officials that she had been scammed. They didn’t believe her. They cuffed and shackled her instead like a criminal. Home became a cell inside a detention facility in Eloy, Arizona. Her bond was $20,000.

These were some of the stories heard by the 22 of us who traveled to Tucson Oct. 18 to visit organizations that support immigrants. Mennonite Church USA, Pacific Southwest Mennonite Conference, and Mennonite Central Committee West Coast organized our two-day trip. We visited Casa Alitas, a shelter run by Catholic Community Services of Southern Arizona, that helps asylum seekers. At Shalom Mennonite Fellowship, we heard about the work of the Florence Immigration and Refugee Rights Project, which provides free legal services to those in immigration custody. Also, we heard from the Tucson Samaritans, a group that attempts to prevent deaths in the southern Arizona desert, by placing water and supplies along treacherous trails.

From these groups we learned the current immigration crisis is essentially a bipartisan failure of the U.S. government. “Build that wall” was a successful campaign strategy for President Donald Trump, however, President Bill Clinton actually built them first. Instead of seeking economic solutions to improve all lives throughout North and South Americas, the U.S. government’s “prevention through deterrence” policy erected walls and barriers to force desperate migrants to travel the most treacherous terrains between Mexico and the U.S. Brian Best of the Samaritans said volunteers have placed more than 600 crosses to mark corpses in the desert. He projected on an overhead screen a harrowing graphic of red dots on a map representing the estimated 4,500-plus unidentified bodies found in Maricopa County, Arizona. Thousands of nameless people.

“Why is it that we Americans, particularly we Christians, tolerate these deaths?” I thought to myself.

Delle McCormick of Casa Alitas, explained that as long as America retains an economic system that, like slavery, relies upon cheap labor, there will be stories of pain and deaths of nameless people. Listening to McCormick describe the courageous and compassionate ministry she and other volunteers are involved in, I also felt their heartbreak. They know they are only helping to ease the pain of a comparative few.

Before arriving in Tucson from Phoenix, the learning group stopped to pray outside of the Eloy Detention Center. Photo by The Mennonite.

It is well-known that America’s immigration system was broken from the start. In this year that the U.S. is remembering 400 years ago in 1619 when the first enslaved Africans were brought to English North America, it is evident that today’s immigration crisis is rooted in America’s same unresolved sin. In the beginning, indigenous peoples were violently removed and resettled. Enslaved Africans were dehumanized, brutalized and commodified. Today’s migration crisis, which is worldwide, is rooted in the same inhumanity that was sanctioned by the church – racism.

A historian once told me that current disputes are usually about past arguments that were appeased, but never truly resolved. This is certainly true for families and church organizations. The immigration crisis is still about who belongs to the American family and who is not accepted.

Jesus Christ sacrificed so that our names might be accepted in The Book of Life. He embodies true justice and equality for all. He confronted unjust rulers who oppressed people. His church must commit to doing the same – in this case comprehensive, fair, humane immigration reform.

Would these mass tragedies of nameless people in the desert be tolerated if their names were actually more like the names I used earlier – Carl, Orland, Beth and Rose? Or is the passive indifference because they are actually Carlos and Carlito of Nicaragua, Orlando and Bethsaida of Guatemala, and Rocio of Bolivia?