By Gordon Houser

This piece was originally published in The Mennonite. Find reflections from other participants in the Mennonite Church USA Migrant Learning Tour that took place Oct. 18-20 in Tucson, Arizona, at mennoniteusa.org/tag/migrant-learning-tour.

On the way from Phoenix to Tucson, Arizona, our car stopped on a small highway, far from any town. Before us, a multitude of lights shone like a small city in the desert darkness, its concrete buildings surrounded by fencing. Inside this complex of prisons is an immigration detention center, housing some 1,500 immigrants. The next two days, we would encounter real people and hear stories that brought some reality to those distant numbers.

Twenty-two of us traveled to Tucson on Oct. 18, following the Constituency Leaders Council, a semiannual meeting of Mennonite Church USA conference leaders, constituency group members and agency personnel, to visit Tucson organizations working to support immigrants. The trip was organized collaboratively by MC USA, Pacific Southwest Mennonite Conference and Mennonite Central Committee West Coast.

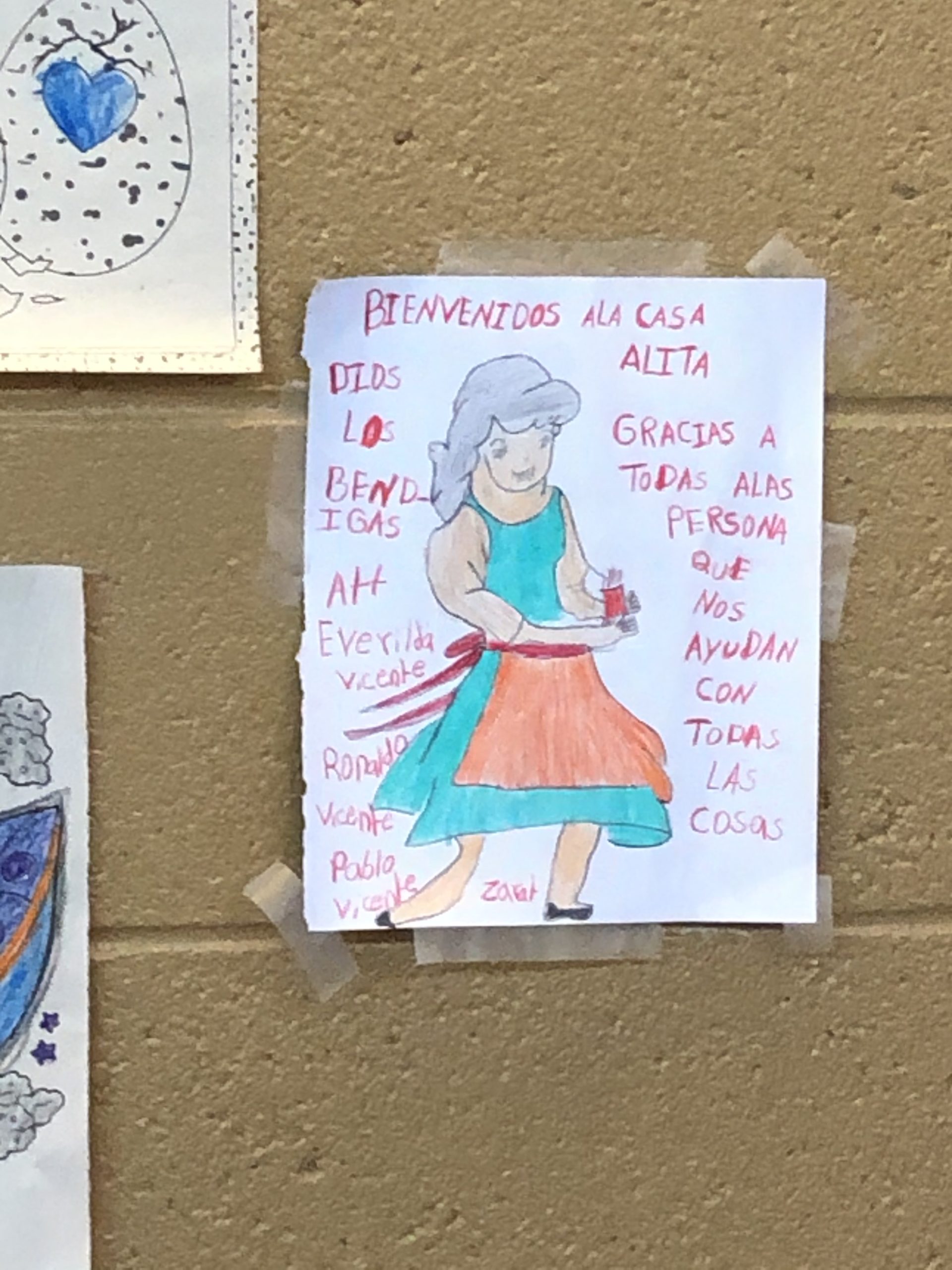

Casa Alitas

First stop on Oct. 19 was Casa Alitas (“house of little wings”), a program run by Catholic Community Services of Southern Arizona. This shelter, which had been housed in a former monastery but now is repurposing what was designed as a detention center in Tucson, offers refuge and hospitality to recent migrant families who are seeking asylum. The families there have been processed by the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and gained humanitarian parole, which allows them to stay in the country legally until their asylum request is processed.

Delle McCormick, a retired United Church of Christ minister, met our group and related some of the program’s history. She told us she has been involved in immigration ministries for 21 years, including time spent in Mexico. In 1989, she said, she went on a mission trip that “blew my theology out of the water.” She realized, she said, that “we need to get our people to take steps closer to what’s happening.”

McCormick sees shelters such as Casa Alitas, which opened in 2014, as “a powerful antidote to the fear we see today.” People of all persuasions, including some who voted for Trump, religious and nonreligious, volunteer there.

Occupancy at the shelter used to be as many as 500 people per day, and in the last year they’ve seen 18,000 people, she said. But now people are being detained in large detention centers, and the numbers are about 30 per day. Most of the families are from Guatemala, Mexico, Honduras, El Salvador, Brazil and Romania and usually stay between one and three days.

As McCormick showed us the shelter’s store of free clothing, we met Carlos, Carlita, his wife, and their son Carlos, 14, who were from Nicaragua. Carlos said he fled with his family out of fear of the government. “There are no gangs there,” he said. “The government is the gang.” They were on their way to Michigan. Ulises Arenas of Iglesia Menonita Hispana, a member of our group, prayed for the family as we all surrounded them, many of us in tears.

Later, we met another family of three—Orlando, Bethsaida, his wife, and their 3-year-old daughter—who were from Guatemala. Orlando had been shot five times, and some people called him to say he could not return home. After a week in the hospital, he left with his family. It took them 13 days to reach the shelter.

“The important thing is to give yourself to God,” he said. “We didn’t come here to do any damage,” he added. “We want to work.” They were on their way to Nebraska. Again, Arenas prayed for them while we gathered around.

McCormick told us that when people come to the shelter, she talks with them and invites them to breathe. They pray aloud and weep, she said. Many have experienced great trauma—including rape, kidnapping, seeing others killed—and are starving. At the border, they’re given burritos, which they don’t eat because they’re rotten. Casa Alitas gives them water, soup and sandwiches.

Florence Project

After lunch, we stopped at Shalom Mennonite Fellowship, where we heard from Alvaro Gonzalez, who works with the Florence Immigration and Refugee Rights Project (FIRRP), which provides free legal services to men, women and unaccompanied children in immigration custody in Arizona.

He told us the story of Elbia. She tried to escape an abusive relationship. After several years, she fled, sought asylum and was transferred to an immigration detention center in southern Arizona. She finally won her case in 2017.

Gonzalez said 86% of the detainees come to their court cases unrepresented due to poverty, and they have no right to a public defender. FIRRP has more than 100 people on staff, working in multiple areas. He noted the impact of the current U.S. policy on immigration: family separations, increased numbers of people in detention, weeks-long waits at the port of entry, no periodic bond hearing, rapid and sweeping changes to immigration law, and rhetoric aimed at creating xenophobia.

Gonzalez, who is part of the Deferred Action on Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, said migrants under 18 are taken to shelters, but as soon as they turn 18, they are placed in handcuffs and their ankles shackled and taken to a detention center. In 2018, he said, 21% of those seeking asylum got it.

Samaritans

Next we heard from Brian Best, who volunteers with Tucson Samaritans, whose mission is to save lives in the southern Arizona desert. He said U.S. policy since the Clinton administration is “prevention through deterrence,” trying to make the journey across the border so difficult that people won’t try it.

He showed photos of the border wall being built but also enhanced with concertina wire. He said the border patrol uses cars, ATVs, towers, drones, helicopters and ground sensors to deter people. Samaritans and the organization No More Deaths leave bottles of water along the border, and they’re always eventually used.

Drug cartels charge people to cross. This used to be $4,000-$5,000; now it’s $10,000-$20,000.

“The border patrol is a huge danger to migrants,” Best said. In order to get enough workers to meet the new demands, they’ve lowered their standards for employment. “Its culture diminishes people’s humanity,” he said, both the migrants and the border patrol agents. These agents have killed migrants over 70 times, Best said.

Joining the border patrol agents are vigilantes who act on their own.

Other deterrents include thorny and poisonous plants that can cause excruciating pain and animals such as rattlesnakes and scorpions.

A Samaritans volunteer has placed more than 600 crosses where migrants have died. And the Colibri Center for Human Rights, where Best works, has collected more than 4,500 missing person reports in one county alone and is seeking to match names with remains that have been found.

Death is the ultimate deterrence, Best said. “This is our government’s intention.”

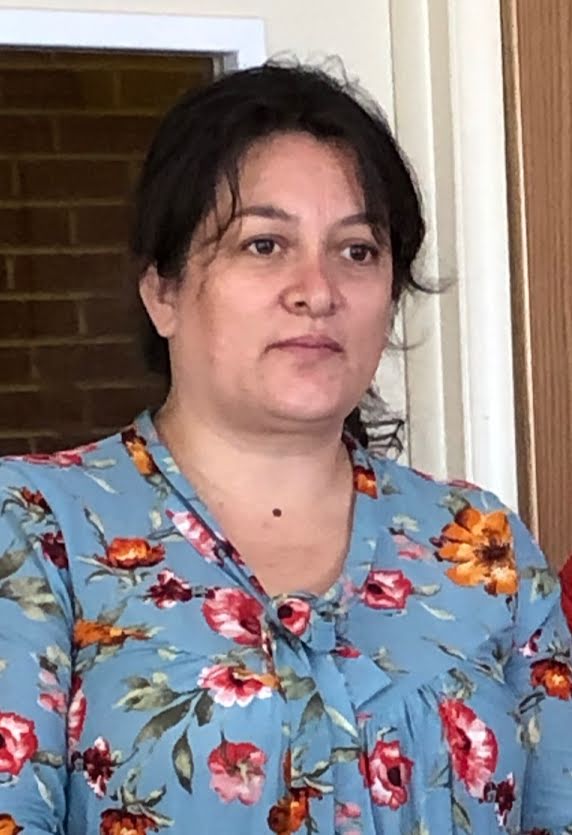

Rocio

On Oct. 20, we joined Shalom Mennonite’s worship service, then heard Rocio’s story. She said she came to the United States from Bolivia in 2014 on a tourist visa. She had a job offer in California but learned she had been lied to. She worked for a man but wasn’t paid. When she tried to leave for Bolivia, a friend lied to her about the date of her flight, and she missed it. At the border, she told the official what had happened, but he didn’t believe her. She was arrested for staying beyond the limit of her visa and put her in a cold cell block for five days.

She said being in a place where people were crying and she had no contact with a lawyer was hard. In Bolivia, they hadn’t heard about the situation here. Eventually someone believed her story, but she had unwittingly signed a deportation order. She and others were handcuffed and shackled and put on a plane.

They arrived at a prison with barbed wire on the walls. They gave her a number and a uniform. She met people from all over the world—old, young, mothers, sisters, grandmothers. Some had been living in extreme poverty.

She learned she needed a sponsor, but she didn’t know anyone in this country. Later, she learned about FIRRP and met with a lawyer, who told her to apply for a human trafficking violation.

She heard about Shalom’s visitation program and wrote to Tina Schlabach, co-pastor of the church. Schlabach visited and wrote her. Others visited and accompanied her to court. Some gave her money.

She grew spiritually, she said. “I was in the hands of God.” For a detainee, there are no rules, she said. A criminal usually knows how long they have to serve, but those in detention have no idea.

In court, the judge told her she could only leave under bond, which was set at $20,000. The visitation program doesn’t have money, but two people each donated $10,000 for her bond, and after two years in detention, she was free.

Two months later, she won her case and returned the bond money to help others. She got a job and lives in Tucson.

Now she works with the visitation program and every Friday goes to the detention center where she was held for two years. Now that she knows what’s happening, she wants to help others.

She said she believes God touches hearts. “We can share that this is happening,” she said. We can form groups and write cards to detainees. “It’s a blessing to receive a card,” she said, since it means a person has not been forgotten.

Following these visits, immigration was not just an issue to discuss or a matter of statistics. It had a human face. Human faces, names: Carlos, Carlito, Orlando, Bethsaida, Rocio.

“Welcome the stranger” is a command in Scripture. But these are not strangers. All the ones we met — and many more — are our brothers and sisters in Christ. Loving our neighbor demands that we take action.