Sarah Augustine is the co-director of Suriname Indigenous Health Fund, a private international charity, and Professor of Sociology at Heritage University where she is also the Director of Student Spirituality. Over the next several months she’ll be writing a special blog series on the Doctrine of Discovery.

Sarah Augustine is the co-director of Suriname Indigenous Health Fund, a private international charity, and Professor of Sociology at Heritage University where she is also the Director of Student Spirituality. Over the next several months she’ll be writing a special blog series on the Doctrine of Discovery.

Last week, my local newspaper published a special edition to the Sunday paper entitled, “Stories from our Families.” It included several dozen stories recounted by my neighbors in the small farming community where I live with my husband and son. Many told of the proud legacies of families who settled this valley more than 150 years ago as Washington was established as a state. Together, these stories weave a tapestry of history, land, struggle and pride.

As I pored over the words and pictures of neighbors, I was reminded of the absence of such stories in my personal history.

Both of my parents were orphans.

I grew up without extended family, without roots. Like many Indigenous people in the United States, I have little contact with my historical homeland, and no legal claim to tribal affiliation. I lack the legitimacy of a federal identification number. My lineage is similar to Indigenous people throughout the Americas.

This is the context in which I experience the Doctrine of Discovery. I am a displaced person.

When I was a teenager, I struggled to hide the poverty and dysfunction in my family. As a young woman, I worked to forget my childhood, chalking-up the shameful want and chaos of my youth to poor personal choices on the part of my parents.

I began working for money to support my family at age 14. I cared for a violent and unstable parent from that age, a task that included working for money, caring for other children, negotiating with landlords and employers and even posting bail. There were no grandparents, aunts, uncles or cousins to call for help.

I was not able to see my own story as part of a larger story, where the histories and actions of my parents were shaped by national and global policy, until I began advocating for Indigenous Peoples.

Like all Americans, Indigenous and Settler alike, I am a product of the Doctrine of Discovery.

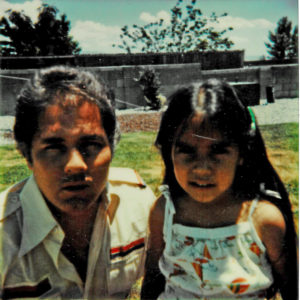

My father’s people come from the hills of what is now referred to as Northern New Mexico. However, my father was removed from his family. He was separated from his mother at birth and placed in an urban Catholic boys’ home. He never knew his family. He endured forced labor, neglect and abuse in the institution where he grew up, and struggled with trauma-induced schizophrenia throughout his adult life.

My father’s people come from the hills of what is now referred to as Northern New Mexico. However, my father was removed from his family. He was separated from his mother at birth and placed in an urban Catholic boys’ home. He never knew his family. He endured forced labor, neglect and abuse in the institution where he grew up, and struggled with trauma-induced schizophrenia throughout his adult life.

There are many possible reasons for why he was separated from his kin, language, land and culture.

The Assimilation Era of American policy toward Indigenous Peoples (1887-1934) sought to “civilize” entire generations of Indigenous children by removing them from their families and educating them in Christian boarding schools far from their homes.

Children were often separated from their communities and families for years at a time, and endured corporal punishment, overwork and abuse while denied the basic rights to speak their native languages, practice their cultures or worship according to their traditions.

There were other forces at play as well. The Los Alamos laboratories, along with the atomic hope to end World War II, were birthed in the remote desert-mountain country where my father’s ancestors had lived and died for millennia. My father’s birth coincided with the war and its devastating effects on his community of origin. Not only did the United States military occupy our traditional homeland as a matter of national security, but also denied the existence of the sovereign nation that dwells there.

There were other forces at play as well. The Los Alamos laboratories, along with the atomic hope to end World War II, were birthed in the remote desert-mountain country where my father’s ancestors had lived and died for millennia. My father’s birth coincided with the war and its devastating effects on his community of origin. Not only did the United States military occupy our traditional homeland as a matter of national security, but also denied the existence of the sovereign nation that dwells there.

Roosevelt’s Termination Era of policy toward Indigenous Peoples (1945-1961) was the last stage in a process to eradicate Indigenous Peoples from the United States.

The stated goal of this policy era was to terminate the legal existence of tribal governments. Even if my father had remained with his mother and family, he would not have had title to his traditional lands, either individually or corporately. The wealth intrinsic to our homeland passed into the hands of others.

Perhaps these are reasons why my father was removed from his community, and why I have no story to share with the local paper.

This legacy of displacement has emotional and spiritual consequences for my whole family; I grew up without a history, without extended family, without identity.

It also has financial consequences.

In the United States, wealth is most often accumulated over generations, passed down through college tuition, help with home ownership via down payments, and inheritance of land, investments and savings. While settler communities have passed down the wealth and benefits of homesteading histories, many Indigenous families are left without resources or origin story.

Funding my own education has been my responsibility alone. Establishing a home and a future for our son is something my husband and I must do without support from past generations.

Funding my own education has been my responsibility alone. Establishing a home and a future for our son is something my husband and I must do without support from past generations.

Like me, my son will grow up without knowing his grandparents, their stories or the stories of their people.

Had my father remained with his family, perhaps I would have a story to share with the local paper parallel to the ones shared by my neighbors. But even then, instead of reinforcing an identity of settlement, grit and success, it would be a story of loss, resilience and perseverance. Because of my father’s displacement, he, I and my son are deprived of this basic inheritance.